| Introduction | ||||||||||||||||||||||

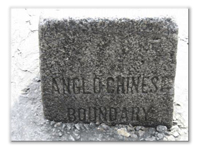

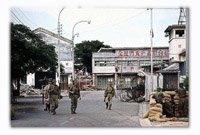

During the previous fortnight I had been following the final chaotic days of the South Vietnamese nation when the Viet Cong decided on an outright attack on Saigon, and I thought "What a catastrophic turn of events, how did it ever come to this ?" Their recent shellings, atrocities and massacres in the surrounding provinces, disregarding the terms of the 1973 Paris peace agreement as on previous occasions, spelled disaster for Saigon this time. It didn't help either that the American ambassador Graham Martin was reluctant to order an evacuation of his embassy until the situation was hopeless "for fear of spreading panic". He had also been hoping that further negotiations might halt the Viet Cong advance. No such luck and panic to escape their clutches did spread across Saigon, especially when it became known that the President of South Vietnam had himself fled on 27 April leaving a new Vice-President in charge. Ambassador Martin was one of the last Americans to be airlifted from the embassy, just hours before the surrender of the nation by a South Vietnamese General on 30 April, 1975. Another to flee on the day of the surrender was Tran Dinh Truong, the owner and CEO of Vishipco Line, the largest shipping company in South Vietnam, but at least he left instructions to his trusted employees to evacuate as many refugees as they could in the Line's remaining vessels. His company had made him a fortune by re-supplying the American forces with all kinds of cargo needed to pursue the war and so resettlement in the USA must have been a formality. That was his aim as he first headed for Manila with his wife and four children in one of his own vessels and he was later to make another fortune in the USA, not in shipping but in the hotel business, much of it in New York.

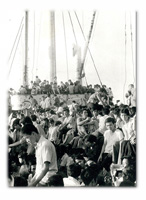

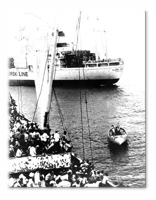

One of the freighters he left behind was the m.s. "Truong Xuan" and on 30 April, the day of the surrender, it managed to sail from Saigon with 3,628 refugees crammed on board and just a skeleton crew. However, on reaching the international waters of the South China Sea after sporadic engine failures and once running aground and being hauled off by the brave helmsman of a tugboat, it ran into really serious trouble with water rising in the engine-room because the pumps had stopped working. In the opinion of its captain Pham Ngoc Luy, no amount of manual effort would prevent the vessel from slowly sinking or worse still, capsizing with huge loss of life. So Captain Pham put out a distress signal on 2 May and Captain Anton Olsen of the Danish container ship m.s "Clara Maersk" answered it. He was en route to Hong Kong and luckily for the refugees, without containers which had just been delivered to Bangkok. After three hours pinpointing the stricken ship's exact position (due to the original SOS giving the wrong coordinates) the "Clara Maersk" came alongside. The rescue occurred at 8°54' N 107°02' E. On humanitarian grounds Captain Olsen agreed that everyone on board could be transferred to his vessel and despite the increase in load to twice its normal limit, he was able to guide it in calm seas all the way to Hong Kong, docking there late on 4 May. Captains Olsen and Pham and their crews had undoubtedly saved thousands of lives.

Once the Hong Kong Government had agreed that this first massive number of Vietnamese refugees could stay in Hong Kong until being resettled, they disembarked and were taken to two camps hastily prepared for them in the New Territories and one temporary one in Harcourt Road on Hong Kong Island. Breaking these numbers down, just over 2,000 went to the recently vacated Army camp at Dodwell's Ridge, 1,055 to a camp in Sai Kung and 513 single men were moved from Harcourt Road to Sek Kong Camp when spare barrack accommodation was made ready for them. The most reliable "Clara Maersk" total handled by these first camps, including new births, is one recorded by David Weeks, a former Hong Kong policeman who at extremely short notice became the manager of Dodwell's Ridge Camp. In a letter he sent to Captain Pham in May, 1976, the combined figure was 3,953 and by then all but 35 had been resettled in fourteen democratic countries. That total also represents the highest number of persons ever rescued at sea off one ship. Subsequent Vietnamese "boat people" were not universally so lucky, either at sea or in being resettled quickly and often had to spend many years in Hong Kong's closed camps.

Her Majesty the Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh would have been given the news of the arrival of the "Clara Maersk" by a hard-pressed Governor Sir Murray MacLehose for by a remarkable coincidence they too had arrived in Hong Kong on 4 May at the start of their first Royal Visit. Her Majesty was later thanked by Captain Pham for having helped to expedite the resettlement of this first huge influx of refugees but typically, in her reply, she took no credit for it, merely wishing everyone resettled a happy future in their new countries. One of three babies born at sea was named Chieu Anh and she was to write her very moving life story some forty years later. This can be found on her Chieu Anh - Truong Xuan Baby - Born At Sea.. Predictably her absolute hero is Captain Pham who went on to be the founder of the Vietnam Human Rights Network in the USA in 1994, his actions in rescuing everybody having already been recognised by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). His own hero is Captain Anton Martin Olsen (1921-1996) who was made a Knight of the Order of Danneborg by Queen Margrethe of Denmark for his humane deed. Captain Pham honoured his grave in the Faroe Islands in 2009 and he himself, born in 1920, sails on into his nineties in Virginia. What a remarkable life for an outstanding man who is also the inspiration behind the 2010 production of a magnificent 628-page book entitled "Truong Xuan - Journey to Freedom". As well as its numerous stories and photographs about this momentous journey and the lives of these first fortunate refugees in their new countries, it also fights the corner of millions more displaced South Vietnamese who were not so lucky.

David Weeks' total of 3,953 probably included 70 who arrived at Dodwell's Ridge Camp from Shaukiwan Police Station late on 6 May and this is where I enter the story as I then happened to be the officer-in-charge of this Sub-Divisional Station in the northeast of Hong Kong Island. At about 0800 hours that morning my Duty Sergeant reported to me that he had just received a message from a local resident saying that a large number of Vietnamese refugees had just gathered in his garden. They had fled Saigon when the Viet Cong entered the city and two fishing boats had brought them to Shaukiwan. "Distressed refugees, what an achievement, must take care of them, extraordinary, get it right"; all these thoughts crossed my mind.

"Tell the gentleman", I said to the Sergeant, "that we will bring them here for processing and also tell the Barrack Sergeant he is to arrange their transport and set up benches, tables, chairs and a few desks in the shady part of the compound. And also you can warn the kitchen that we will need extra food and water, how much I don't yet know. I'm on my way to see them and the boats." Before leaving the station I broke the news to my Divisional Superintendent John Macdonald and he was to set the wheels in motion to basically treat our police station as a mini Port of Entry for the day, or for as long as it took the Government Security Branch to arrange their next abode. In the garden of a house near the Shaukiwan harbour were 70 outwardly calm but tired Vietnamese and the basics of their journey were described to me. The two fishing boats were shrimp trawlers owned by a joint South Vietnamese/Hong Kong consortium which would explain how their skippers knew their way around the far reaches of Hong Kong harbour. I learnt more on the way to the boats. The owners and crews had been preparing for their escape by sea while the Viet Cong were closing in on Saigon and most of those who managed to do so were their families or friends. But on the way down the Saigon river they had been boarded by a group of about a dozen South Vietnamese military officers taking flight in speed boats which were obviously unable to go far before running out of fuel. These officers were relieved to hear that the trawlers' skippers hoped to reach the safety of Hong Kong and settled down for the journey. This was uneventful until the engine of one of the boats failed and both had to be strapped together. Fuel was transferred from the ailing boat to the other one when needed and in relatively calm seas they were able to reach Hong Kong by the early hours of 6 May.

I asked if any of the military officers were still with the main group. "Oh no", I was told, "they said they would take public transport into the centre of Hong Kong and seek asylum at the American Consulate". I later heard that they had indeed jumped on a Public Light Bus (PLB) in the centre of Shaukiwan but I could not confirm anything about their subsequent movements. My supposition was that the Consulate would have quickly had them airlifted to Guam which was to become the main American staging-post for tens of thousands of the early refugees, and a magnet for the opportunistic Hong Kong goldsmiths hoping to buy their gold in exchange for cash. John Macdonald and I then examined the boats. All appeared as expected with fishing boats except for several small arms and some loose ammunition scattered around one of the boats. I was told that they had been jettisoned by the military officers before catching their PLB, and wisely so. I later passed these on to the Force Armourer apart from several heavy cartridges or grenades which the Force Bomb Disposal Officer took away for disposal. As for the actual boats, Hong Kong members of the consortium took responsibility for them and I assume that after repairs and servicing they carried on trawling in the peaceful areas of the South China Sea. It would also have made sense for the Vietnamese fishing families amongst the 70 to have applied for resettlement in Hong Kong. At least 145 of these first thousands of refugees did apply for resettlement in Hong Kong and were accepted.

Returning to the police station, I found the processing under way exactly as if the group of 70 had arrived at a normal Port of Entry and this was to carry on for most of 6 May. The Government's Secretary for Security had been advised of the situation and officials from the Immigration, Customs and Excise and Port Health Departments quickly arrived to perform their normal duties. During the afternoon I learnt that after processing them, all 70 were to join those who had been sent to Dodwell's Ridge Camp from the "Clara Maersk" the previous day. During processing, and with the aid of an interpreter, I was able to chat with some of the heads of the families. They were understandably still tired and anxious but also relieved and grateful to be in safe Hong Kong hands. I clearly remember one particular family comprising two parents, nine lovely daughters aged from about ten to twenty years and two of their grandparents. Putting myself in the father's shoes, how much more traumatic could it have been for him to be firstly uprooted from his native land and then to undertake a hazardous journey with such a large family and an uncertain future ahead of them? I took my hat off to him and wished him and his family a good and early resettlement and a bright future, as I did with all of the others as they left Shaukiwan for Dodwell's Ridge Camp that evening. The next day I contacted the Camp manager David Weeks and he told me they were settling in well with all the others and just glad to be in a safe and healthy environment again.

In 1976 the Hong Kong Government applied to the UNHCR for more material aid and a faster processing of the remaining refugees at Sai Kung and Sek Kong Camps, Dodwell's Ridge having closed as early as October 1975 and by 1977 all had been resettled, mainly to the USA, Canada, France, Australia, Hong Kong and Denmark. As at 31 May 2000, when the last Hong Kong refugee camp closed in the New Territories, a total of 143,700 from both South and North Vietnam had been resettled in the free world, and over 67,000 repatriated back to Vietnam, the last of them forcibly by the post-colonial SAR Government. These are the bare statistics of a generally very awkward twenty-five year period of Open and Closed camps but what a tremendous job the UNHCR and the Hong Kong Government and its disciplined services managed to do in very difficult circumstances after the comparatively easier task of handling the first huge numbers off the Clara Maersk, not that their resettlement was politically trouble-free either.

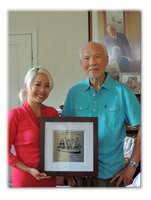

Thanks to the Internet, many records of this period can be studied, including the experiences of numerous passengers on the ill-fated m.s. MS Truong-Xuan and their subsequent resettlement. One of the luckiest passengers was nine-year-old Debbie Nguyen whose story of her family's eventful journey starting fifty miles outside Saigon was to appear in the book "Truong Xuan - Journey to Freedom" that I have already mentioned. Her family of eight (parents, five daughters and a son) was blessed with enormous slices of good luck along the way, culminating in their quick acceptance for resettlement by Australia. On 20 June,1975 and with few possessions, Debbie's family and other relatives left Sai Kung Camp for Sydney and as of 2016 their extended family has more than tripled in size. The first addition was Margaret, a fifth sister for Debbie who was born just a month after they arrived in Sydney. The press gathered to congratulate her parents, especially her amazing mother who had been heavily pregnant with Margaret on board the "Truong Xuan". The whole family continues to treasure the opportunities and the way of life that have luckily come their way and will always appreciate that they owe their lives and freedom to the skill and humanitarian deeds of two outstanding ships' captains Pham Ngoc Luy and Anton Martin Olsen. Debbie Nguyen is now an accountant, married with three children of her own and when she read in my email that I hoped that my own little story may one day also be published she very generously sent me a copy of the marvellous book "Truong Xuan - Journey to Freedom". It is "The Commemorative Book of the Vietnamese Truong Xuan Boat People" and was 35 years in the making. Inside the cover she has written "Thank you for being part of our life's long journey". I think Sydney is very lucky to have Debbie and her outstanding family in its midst. I will also always remember the gratitude shown to the staff of Shaukiwan Police Station by the group of 70 refugees who, in common with those from the "Clara Maersk", would have suffered many an anxious moment in their quest for freedom. It was a privilege to briefly look after them on 6 May, 1975 and I hope that they went on to prosper in the countries that accepted them. |