| Acknowledgements | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

I am particularly indebted to Sir Richard Turnbull, GCMG, for his encouragement and continued interest ever since the idea of writing the book was first conceived. He has, very patiently and painstakingly, read through the many pages of the rough manuscript on more than one occasion, and offered some very valuable and helpful advice at every stage. For the great interest he has shown, and particularly his willingness to write the Foreword to my humble effort, I can only say, ASANTE SANA BWANA. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Foreward by Sir Richard Turnbull, GCMG | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

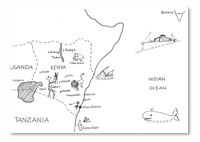

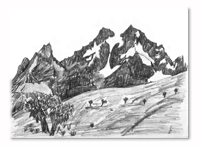

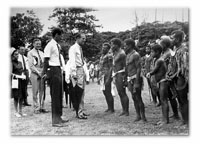

| This is a book that is going to appeal to a wide range of readers. First, there will be those other 'Mabwana Karani' Mervyn Maciel's fellow- District Clerks and Cashiers, who saw service in the Turkana and Northern Frontier Districts, or in any of the smaller stations of up-country Kenya. With them will be their many relatives and collaterals broadly scattered from Bombay to Birmingham; for the Goan people are a closely-knit community and with their long tradition of clerical service are to be found not only in the courts, offices and counting-houses of Goa and India, and a score of places in East Africa, but in this country as well; and, indeed, in any place where loyalty, industry and scrupulous dependability are properly valued. Then will come those from whom Mervyn learnt his trade, and those that he, in his turn, instructed in the arts and crafts of the clerical side of the Provincial Administration: and, after them, ex- Government Servants of Colonial days hankering for a detailed account of the routine of a District Office, and for a description of the everyday duties that fell to the charge of a District Commissioner in a small station. There will, too, be those that duty or relaxation have taken to the outlying parts of Kenya, and who still experience a nostalgic pang at the sound of place-names such as Wundanyi, Voi and Taveta; Amudat, Lodwar and Lokitaung; and Laisamis, the Kaisut, Gof Bongole and Loiangolani. Finally, there will be those such as myself, eager to refresh recollections of earlier days, and to read of old friends, many, alas, no longer with us but still remembered with affection, who appear in Mervyn's narrative. If the introduction of a personal note may be forgiven, I should like to mention 'Miti' Wood, the guiding hand in all matters concerning personnel, and the author of Mervyn's Letter of Appointment; Ayub Ali, that great gentleman of the Establishment section of the Secretariat; Willie Pereira, whom I first met at Garba Tulla close on fifty years ago; Germano Gomes, a partner of many arduous fourteen-hour days when he and I were caring for that Ethiopian host which had sought refuge in Kenya from the Italian invasion, and Francis da Lima, a most valued colleague and companion to whom I am indebted for years of painstaking help in my Isiolo office. These and a dozen others all figure in the pages of the book. From the first sentence of the Introduction to Bwana Karani until four-fifths of the way through the book, you will be reading about the Provincial Administration; and most of the characters that you will encounter will have been members of it. So it is proper that I should give you a brief description of what it was: A Provincial Commissioner was, within the limits of his Province, the principal executive officer of the Government, and was personally and directly responsible to the Governor for the peace and good order of his Province and for the efficient conduct of all public business therein. It was his duty to supervise not only the work of his administrative staff but also what was done in his Province by all Departmental Officers. The Provincial Administration was the machine by which the Provincial Commissioner's responsibilities were put into operation; in addition it was both a chain of command and a service — a particularly elite one. Let me not forget, though, that twenty years and more have elapsed since the end of the Colonial regime, and in this time — amounting to four or five school generations — what were once the commonplaces of everyday living have taken on the aspect of legend; and it is not unlikely that the majority of those that read this book will know nothing of how the old Colonial machinery of Government worked, or of the people whose efforts kept it ticking over. I spent such a large part of my life being a District Commissioner, and sharing the problems and the shop of other District Commissioners, rejoicing with them in their triumphs and condoling with them in their disasters, that it is, I suppose, not unreasonable that I should devote a paragraph or two to explaining what a District Commissioner was and what it was he did. In his particular area a District Commissioner was the senior representative of the Central Government and, under, of course, the general supervision and control of the Provincial Commissioner, was responsible for the peace and good order of his District, and for the preservation of law and order within it. By the expression 'good order' I have in mind the co-ordination, in the field, of the activities of the various Ministries, and the fulfilment of the functions of those Ministries that had no representative in the District. A District Commissioner had to ensure the effective execution of the Governments policies by making certain that the representatives of the Ministries concerned were working smoothly together, and that progress was not being hindered by Departmental rivalries or by the personal idiosyncrasies of individual officers; and, as I have indicated, he had through his own District staff to undertake the duties of those Ministries that had no staff of their own in the field. As you will see from what I have written, it was necessary for a District Commissioner to have a good grasp of the technical problems facing the various Ministries, and to be able, by the exercise of tact and diplomacy and by a well-informed and sympathetic approach, to bring about a harmonious dovetailing of the various aspects of the Government's activities. He had, further, a whole range of routine responsibilities, such as the preparation of annual estimates of revenue and expenditure for his District, for the control of expenditure, and the bringing to account of public funds, and for the development and control of African Local Government bodies. He also had to be a practical man, for in a small station he had to supervise the siting, construction and maintenance of the Government buildings; to purchase station stores; and to oversee the rationing arrangements for the Tribal Police, the Prison and the local school. He might, too, have had to select suitable runways for emergency air strips and to supervise any construction work that was necessary; and hold himself in readiness to conduct, in co-operation with the Locust Directorate the campaigns that had so often to be undertaken against this scourge. These internal administrative duties when added to his more general commitments, such as liaison with the Ministries, made up a corpus of widely diversified responsibilities, scarcely one of which did not involve, in its handling, clerical work of one sort or another; and rare was the District Commissioner who could not congratulate himself on having at his call a clerical staff that was both professionally expert and personally dedicated to the efficient and punctual completion of the tasks with which they were concerned. Court records had to be maintained, prison registers kept up to date, cash books and vote books meticulously entered-up, any number of returns submitted, papers properly filed, and a seemingly endless flow of correspondence maintained with various headquarters offices. It would be tedious to itemize in detail all the duties that fell to the District Clerk and the Cashier; it should be enough to say that, although these small stations may have appeared to be quiet backwaters as far as the flow of work was concerned, the clerks would, as often as not, find themselves at work in their offices long after they should have been relaxing on the tennis court or in their homes. Yet not once, in all my experience in the field — and, equally, in the offices of the Central Government — did I hear even the hint of a murmur or criticism, let alone an expression of discontent on the grounds of an excess of unrequited overtime. What gifted and conscientious men they were that we had working with us! It was indeed a splendid service — a service to which one is proud to have belonged; and how gratifying it is to hear our author rejoicing at having been a member of it. In the larger sort of District, such as Kisii, where Mervyn served before he was transferred to the Ministry of Agriculture, it was unusual for the various Ministries not to be well represented; and the District Commissioner himself would have had the support of several District Officers. In such circumstances, the business of coordinating departmental activities presented no major problems. The normal procedure was for the senior Departmental Officers to organize themselves into what was known as the District Team, under the Chairmanship of the District Commissioner; and it was in this forum that the proper handling of matters affecting more than one Ministry was debated. By the exercise of common sense, and the adoption of a series of readily acceptable, interlocking compromises, potential difficulties could, as a rule, be satisfactorily side-stepped. There was, of course, enough staff, administrative and clerical, to ensure that any scheme that was embarked upon could be properly supervised and properly maintained. Elsewhere, although the one-man stations that had been fairly common in pre-war days had, by Mervyn's time, virtually ceased to exist, the remote stations of Turkana and the N.F.D. were still run on a shoe-string of manpower. For the administrative philosophy that underlay the governance of these northern areas was based on two principles, neither of which demanded much in the way of technical staff; first, to prevent the weak from being oppressed by the strong, and secondly, to protect the grazing ranges, the well systems and the man-made water pans against destruction by over-grazing and undisciplined usage. In the Frontier Province what mattered was security and the preservation of a proper ecological balance, not for the fulfilment of a conventional urge for economic and social development. As a result Ministerial representation in places such as Lodwar and Marsabit amounted to little more than occasional visits; and the District Commissioner had to make do with his own efforts and those of his District Officer, if he had one, and with what help he could reasonably expect his clerical staff to give outside the scope of their usual duties. It was in circumstances such as these that, during his time in Marsabit, although officially the District Clerk/Cashier, Mervyn found himself taking charge of tax collection and pay safaris, supervising stock sales, and, during the absence from the station of both District Commissioner and District Officer— from time to time unavoidable — carrying out inspections of the gaol and performing other duties that would normally be undertaken by an Administrative Officer. The reader will quickly see that Bwana Karani is by no means wholly devoted to descriptions of the business conducted in a District Office, and of the hour by hour activities of a District Headquarters, from the pre-breakfast inspection of what one might call the domestic economy of the station to the close of public business at whatever hour the climate and local custom and usage dictated, and, in the case of Lodwar and Marsabit, to the sounding of Retreat and the lowering of the standard at sunset. He will find, as well, generous character sketches of local worthies resident in the various Districts in which the author saw service, and of his wide circle of friends both in the small up-country townships and the larger centres such as Mombasa, Nakuru and Kitale; and, amongst other topics of interest, accounts of the long journeys by night that characterized travel in the N.F.D. and Turkana — incidentally, one is amazed that Mr Kaka's vehicles ever contrived to stay on the road — and of the landscapes that distinguished places such as Fergusson's Gulf, the Chalbi and Mount Kulal. There is something of romance, too, with the story of Mervyn's long courtship, chiefly by letter from Lodwar and from Marsabit, of his future wife, the daughter of Mr and Mrs Hermenegildo Collaco of Kitale. They were formally betrothed shortly after the Christmas of 1951, and the wedding held in August of the following year. Their married life began at Marsabit, the bride coping bravely with the problems created by being so very much at the end of the line. It is interesting to reflect upon the extent to which the pair, both individually and together, had benefited from the friendly offices and the staunch reliability of old-fashioned 'transport riders' such as A. M. Kaka, the Pathan, on the Kitale-Lodwar route, and G. H. Khan, the Kashmiri, (affectionately known by us all as 'the Safe Driver') between Isiolo and Marsabit. The Marsabit days which had started with such high hopes were to end under as heavy a cloud as one can imagine; for Conrad, Mervyn and Elsie's second son, was found to be suffering from a heart condition that condemned him to the life of an invalid, and which made it necessary for the parents to seek a posting to some place where medical facilities would be more comprehensive and more easily available than they were at Marsabit. They were loath to leave, but as Mervyn says, "we simply could not afford to risk Conrad's life by remaining in an area which was miles away from a hospital proper." And so, cast down at having to move from a place to which they had become so attached, and burdened with anxiety over Conrad, Mervyn and Elsie made their farewells to the Northern Frontier Province. Mervyn's departure from Marsabit may be said to have ended the days of his 'Karaniship'; for after a brief spell in Kisii — a spell which sadly saw the death of young Conrad — he applied, and successfully, for the post of Executive Officer with the Ministry of Agriculture; and having achieved this very real measure of advancement, was appointed to be the Provincial Office Superintendent at Machakos, the duties of which post he combined with those of Personal Assistant to the Provincial Agricultural Officer. He was, as can be imagined, distressed at leaving the Provincial Administration in which he had hoped to remain until the time for his retirement; but it was not long before he came to recognize how substantial were the advantages that attended his new appointment. Being at the Agricultural Headquarters of a populous and rapidly developing Province meant that he came in contact with the Provincial Commissioner and other Administrative Officers of the area, as well as with senior members of the various Departments. He was no longer tucked away at the end of the line. And nobody could fail to be impressed by the quality of the men that headed the Department of Agriculture; it was generally accepted that the Ministry had in its service some of the most brilliant men, in that particular field, in the whole of the Commonwealth. As for the activities of the Department, how could one describe them better than to say that the economic future of the new Kenya depended more upon the policies devised by the Ministry and the efficiency with which they were put into execution than upon any other factor? And Mervyn became as proud of his position in the Ministry of Agriculture as he was of having served in the Provincial Administration of the Northern Frontier Province. Richard Turnbull | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Introduction | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

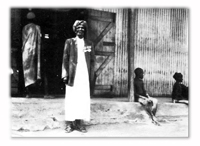

| It has always been my wish to write about my experiences in Africa; this, not so much out of pride for having had the good fortune of working in Kenya's Provincial Administration, an opportunity I often think of as extraordinarily rewarding, but more in an effort to share my experiences with the reader, and with those of my colleagues who may have, like me, enjoyed the delights and varied attractions of a district life. Why the title Bwana Karani you may well ask. To the reader who is familiar with the lingua franca of East Africa, i.e. Ki-Swahili, this will not present any problem. For the benefit of the others, however, I have to explain that the Swahili word karani means 'clerk', and it was in this humble capacity that my working career with the Provincial Administration began. It seemed fitting therefore that this book should bear the title of my very first job. While the literal translation of the title would read 'Mister Clerk', a term which certainly doesn't sound right in English, the courtesy title Bwana Karani was an accepted one, and extended to all such personnel in the civil service and other commercial quarters too. In the Marsabit district of the Northern Frontier Province for instance, one was often referred to as karani guda (senior or chief clerk) or karanidikka (junior clerk). Working in the districts of Kenya was, I must admit, not everyone's cup of tea whereas, working in the N.F.D. (Kenya's lonely and uncompromising Northern Frontier Province) was worse still. Although climatic conditions varied in this vast region of some hundred thousand square miles (twice the size of England), the mode of travel, especially during the period I was stationed there had improved considerably from that obtaining during the time of my predecessors. Some of these journeys were made on foot like the one undertaken by the first Goan District Clerk, a Mr John Fernandes who, Sir Richard Turnbull tells me, marched up with Mr G. F. Archer from Naivasha in 1909! These officials, and many like them who served in the frontier in those early and pioneering days, were almost certainly a special breed of men. The N.F.D. had a certain appeal — an attraction more easily experienced than expressed. It was a compelling place for some of us, undoubtedly a land of scorching heat and inter-tribal hostility, but none of these considerations could dampen my desire to be part and parcel of this Province which had its own mystique.

It is as well to explain here that the life of a Goan (there were more Goans serving in the districts than other Asians) clerk in the Provincial Administration, especially in the N.F.D., was not all honey and highballs; it was tough and uncomfortable, and lacked the variety of a safari; there were the unhealthy climatic conditions that one had to endure in some regions, and many areas were not without their dangers. A former Provincial Commissioner, and one of the 'grand old men' of the N.F.D., Sir Gerald Reece, once said that it was in this Province that 'real life' was to be found. How right he was. For me, the attraction of the N.F.D. was that great feeling of freedom, the sheer vastness of the districts and general spaciousness of the areas. I was also fascinated by the customs and colourful life-styles of the extraordinary tribesmen who inhabited this Province, and quite prepared to leave civilization behind. Despite these considerations, however, many of my friends considered me 'crazy' for volunteering to serve in this remote and, as they termed it, God-forsaken region. Some even felt that it was a sort of punishment to be posted to the N.F.D; but then, does one volunteer for punishment? Be that as it may, I have no regrets. My wife, who shared part of this frontier experience with me, and enjoyed every moment of it — despite having a child with a congenital heart condition to look after, has been very keen all along that I should tell the story of my life in those outlying areas. It is an area which, like the peoples who inhabit it, is fast vanishing. Our children, who have listened to the many accounts of our life in the wilderness, have also felt that the story should be told, if only for the benefit of many who, like themselves, will never experience such a life in today's highly civilized world. With their encouragement and interest, and the backing I have received from many friends and former colleagues, I have finally taken the plunge! The book has a frontier bias, and an Administration bias at that. I make no apology for this, since the best years of my life were spent in the N.F.D. Since part of my service career, especially during the latter years, was with the Agricultural Department, a period which I also enjoyed, I am including a note of the time spent there. I sincerely hope that those of my colleagues who may have at some time or another served in this harsh and rugged corner of the African continent, will be able to relive some of their own experiences of bygone days. For others who have not ventured beyond the 'civilized' shores of Mombasa or the attractions of that great metropolis, Nairobi, I sincerely hope that these pages will provide some insight into the life and conditions under which some of us chose to serve. The book is a collection of real life experiences as far as I can recall these, although I am aware that the picture is by no means complete. I am very conscious of the debt of gratitude I owe to the tribesmen of the various districts I served in. Without them, these pages could never have been born. Mervyn Maciel | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Part One: The Early Years | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

1: From Student to Kenya Civil Servant East Africa, and particularly Kenya, has always occupied a special place in my heart. The fact that I was born in Nairobi, and spent the early years of my childhood there is perhaps significant. This is why I lost no time (even before the results of my Matriculation examination were known in 1947) — in writing to my late father's boss, Capt. R. C. M. Wood (a most lovable man, known to his friends as 'Miti' Wood), to ask if he would be willing to offer me employment in his office. I should explain that my father worked in the Kenya Secretariat for many years until his untimely and tragic death during the war, when he, my step-mother and three very young children (two step-sisters, one aged three and the other a babe of a few months, and a stepbrother who was just one year old) were lost at sea in November 1942, when the ill-fated passenger liner, the SS Tilawa was torpedoed by the Japanese a few days after she had left Bombay for Mombasa. As far as I can recall, this was the only passenger steamer that was destroyed on the India-East Africa route during the war. (See 'In Memoriam' in the Appendices to this book — a tribute to my parents composed on the second anniversary of their death). My father was highly regarded by his superiors and colleagues alike, and friends and relatives always spoke in glowing terms of his simplicity, courtesy and unassuming manner. He was, as I was to hear on numerous occasions later, very efficient at his job, and because of his sheer dependability, always in demand. A first class stenographer (combining the role of Stenographer/Secretary/P. A. in the days before the birth of the female Secretary we now know) he was, at one time, attached to the Governor's Conference Secretariat in Nairobi. Being orphaned at a very early age, and having a younger brother who was still at school, I felt that it was all the more important that I should take on employment as soon as possible. My elder brother Joseph, two years my senior, had also been very patient in delaying his decision to join the Society of Jesus (the Jesuits) until I had first secured gainful employment. Wilfred, my younger brother, who was three years my junior, was fully aware that as soon as I found employment, he would have to move from the school we had both attended in Goa (in the village of Aldona), to one in Bombay where he could be nearer to my elder brother and other relatives. Within a few weeks of my writing to Capt. Wood, I received a very encouraging reply offering me employment at the Kenya Secretariat, as a temporary clerk, at a salary of £120 per annum! (For the benefit of the reader, I am reproducing the original letter I received — see Appendices). At the time, this salary sounded very decent and some of my friends in India, who were receiving a far lower wage, soon set about to calculate the amount I should be able to save on this seemingly 'fat' salary. I was delighted with the outcome of my application and even felt a trifle flattered! The fact that Capt. Wood had requested the Kenya Government Agents in Bombay (Messrs. Mackinnon Mackenzie & Co) to arrange a sea passage for me helped matters no end. There were no 'middlemen' or a host of other obstacles for me to go through. All I had to do was find the fare. The Kenya Government had awarded my brothers and myself, and my paternal grandmother a military-type pension because of my father's death on active service. This pension, together with other assistance provided by my maternal grandfather (a retired official of the Zanzibar Treasury), and my paternal grandmother, went a long way towards helping me in meeting the cost of the passage and other incidental expenses. An uncle from my father's side (Ignatius Sequeira) was a great help in attending to some of the other arrangements. There were many others, including my two brothers, and a host of relatives and friends who played a part in my move. Without their assistance (for which I am deeply grateful), the outcome could never have been so smooth. There is an old saying in my native tongue, Konkani, that those who are orphans have 'a hundred mothers and fathers'. To all those who helped, in however small a way — relatives and friends, and particularly to those who were 'mother and father' to us during those difficult and fateful years, I would once again like to record my deep gratitude. I set sail for Kenya in late September 1947, having spent a few weeks prior to my departure, with members of my immediate family in Goa and latterly in Bombay. Words of advice and caution were given by my grandparents and elder brother too. I was going to Africa where they all hoped I would uphold the good name of my late parents. The parting from my brothers and close relatives and friends was certainly a sad occasion. I was a deck passenger on the B.I. liner, the SS Aronda, a ship which had been converted to a passenger steamer after her previous mission as a troopship during the war. Initial emotions melted away after we left Bombay harbour, and before very long, the impressive gateway of India had faded almost into obscurity; we were now on the high seas with nothing but an endless expanse of ocean all around us. Not another vessel in sight — just miles and miles of deep blue sea. I enjoyed the voyage immensely. I am fortunate in that I am a good sailor who rarely suffers from any form of sea-sickness. I was therefore able to do justice to the mouth-watering and tempting Muhammadan-style menu on board the ship. Being deck passengers, we were not allowed to use the main dining saloon reserved for cabin class passengers. I did not mind this in the least, especially since, as deck passengers, we had the choice of spicy vegetarian or non-vegetarian meals, both of which I enjoy. My appetite throughout the voyage was terrific; here, I must admit to being saddened by the fact that a friend of mine (who was returning to Kenya to take up an appointment as an industrial chemist), was so sick during the voyage, that he often had to spend the greater part of his time in bed. For Joe Sequeira, the very thought of food was revolting; neither could he tolerate the rich spicy aroma of the food which seemed to fill the whole area around the deck. There were times when he would find it difficult to retain even a mere Jacobs cream cracker biscuit! The poor man — I felt truly sorry for him. Late at night I would encourage him to come to the upper deck so as to take in as much of the fresh sea air as possible. Although this little exercise did him a world of good, he never felt strong enough to face a real meal. He would eat morsels of whatever suited him best, and I felt he was wise in sticking to this meagre diet. The voyage took eight days and included a few hours stop-over en route at the delightful island of Mahe in the Seychelles. As our ship anchored at Mahe, small fishing craft raced towards it, almost submerged under the weight of the heavy loads of various curios they were bringing for sale on board the ship. With the Captain's approval, they ran a sort of mobile shop, displaying their varied wares on hastily mounted trestles and tables on the upper deck of the ship. The curios consisted mostly of stuffed tortoises, a variety of sea shells, some very attractive curios made from tortoise shell and an assortment of walking sticks. The fisher folk also did a brisk trade during the few hours that the ship had docked in their waters. Some of the deck passengers were even able to buy fresh fish, and that evening, the whole air around the deck area was laden with the smell of fried fish! On the 6th October 1947 we docked at Kilindini harbour, Mombasa. Here I was warmly welcomed by my cousin (Jock Sequeira and his wife Beryl). They had been in Mombasa for a year, having made the big decision to move out of the Bombay they loved and grew up in — to start a new life and better their prospects in Africa. I felt very comfortable in their small but homely quarter situated at Ganjoni. This house was shared with another Goan family (Mr and Mrs Albert Pereira — the late Albert Pereira, a very likeable person, who worked for Smith Mackenzie & Co). From the time of landing at Mombasa, I became an official of the Kenya Government — at least so I was told! Little did I appreciate the implications of this position at the time, and a friend of my father's — a Mr A. B. Rego, who worked at the Government Coast Agency, felt that I should be 'entitled' to a free railway warrant for the onward journey to Nairobi. I knew nothing about these 'service entitlements'. I was absolutely green from school, and it seemed as though I was entering a new world altogether. As he was not entirely certain about my entitlement himself, Mr Rego cabled the Secretariat in Nairobi; meanwhile, I was asked to postpone my departure from Mombasa until an official reply was received. This suited me fine, and my cousin Jock was happy that things had turned out this way, since he was busy organizing a Variety Show in which he wanted me to take part. HMS Nelson had docked in Mombasa, and several of her Goan crew, whom Jock had previously met, would also be taking part in the show. One of the songs they would be singing was Jock's own composition in Konkani, in which he extolled the contribution made to the Merchant Navy by Goan seamen. A Goan Petty Officer from the flagship — a Mr Nazareth, would also be taking part. As it so happened, despite early approval of my passage from Mombasa to Nairobi, I managed to spend a whole week at the coast and took part in the Variety Show which turned out to be a great success, judging by the number of people who had packed the Goan Institute hall that evening. I could hardly believe that such a successful performance could have been staged at so short notice; where there's a will, there is surely a way! The next day I reported to the Government Coast Agency where I was handed a railway warrant which I later exchanged at the station for a second class ticket to Nairobi. My baggage was weighed and taken away by the railway porter to be stored in the main brake van. I was given a receipt to enable me to reclaim the packages at the other end. My compartment had been reserved, and after quickly checking the Reservations board, I walked up to my coach and off-loaded some of my hand luggage on to the lower bunk. This would be sufficient indication to the three other passengers who would be sharing my compartment, that I had already reserved my seat! The coach itself was immaculately clean, and this impressed me greatly especially since the coaches I had been used to travelling on in India were just the opposite. Even the coach attendants here were smartly turned out and looked very impressive in their well-laundered and starched snow-white uniforms. For a very modest charge (which I was told I would be entitled to reclaim), I obtained my bedding, and later found that the attendant had made my bed up very neatly for the night. I had never before experienced such luxury. The railway station was bustling with activity. There were so many faces to be seen — some happy, others sad (a fairly common scene at any railway station). Porters were busy running up and down the platform with loads of luggage strategically balanced. I often wondered how they remembered to collect the porterage from the various passengers. The great steam engine was hissing and puffing away, and soon I heard the whistle blow; the green flag held out by the railway guard signalled the 'all clear' for our departure. At this stage, and as the train pulled out of the station, three ear-piercing whistles sounded, and with a sea of hands and handkerchiefs fluttering from passengers on the platform, the mighty engine hissed her way out of Mombasa station. The sound of the steam engine pulling the long line of coaches, and belching out clouds of smoke as it raced along, gave me a wonderful feeling. As the train snaked her way, leaving the sea and the palm-fringed coast behind, we passed lush green mangrove plantations. There were brief stops at Mazeras and Mariakani — station names with so much of a coastal flavour. Here, small but very lively crowds of the local Swahili folk would assemble, and there always seemed a festive air about. While some were welcoming home loved ones and friends, others had come to see them off. All along our route, we often passed villagers standing outside their shambas in their colourful dresses and waving happily to the passengers in the train. Such scenes must have been a daily occurence especially since the mail train plied between Mombasa and Nairobi every day. The first visitor to our compartment was the TTE (Travelling Ticket Examiner) — a European; he was later followed by a Goan steward, immaculately dressed in a white suit, and holding a pack of dining-room tickets in one hand. I booked for the first sitting and was given a card, the reverse of which showed the seating plan. One of the catering staff, dressed in a snow-white kanzu and red fez, sounded the xylophone to announce the start of each sitting. A few minutes after this signal, I walked up to the restaurant car along with some of the other passengers; here, we were greeted by the steward and shown to our respective places. Everything appeared so spick and span — from the crisp white damask table-cloth and napkin, to the polished heavy silver cutlery and china — all carrying the railway crest. Adding colour to each table was a tulip vase containing freshly cut carnations which filled the air with their fragrance. How I admired the skill of the waiters in serving piping hot food from a fast-moving and sometimes 'jerky' train. They certainly had a knack in the manner they dished out the food. The meal itself was delicious — a soup as a starter, followed by roast beef and all the trimmings and finally a dessert. The freshly percolated Kenya coffee which followed was a real treat, and its rich aroma was so appealing that I couldn't resist the temptation of having a second cup! I was not able to remain long in the dining car since passengers for the second sitting were now beginning to arrive. I returned to my compartment, and spent some time reading. Our train had now arrived at Voi station — the main junction for Tanganyika-bound traffic. We had to spend some time here while coaches were being shunted on to the right track; it was quite dark by now and there was not much to be seen outside. Because the train was likely to remain here for some time, many of the passengers decided to alight and stretch their legs. I did the same, and when we were all set to leave, I decided to retire to bed. I slept comfortably that night and was awakened very early the following morning by the coach attendant who had arrived with cups of early morning tea. Personally, I was used to having coffee in the mornings, but didn't feel it right to ask for something 'special' just for myself. The view of the surrounding countryside was wonderful. There were the Athi plains just before we came in to Nairobi. All along the route, we saw an assortment of game, notably giraffe and zebra. At Nairobi station to meet me was an old family friend, Louis Borges, whose guest I was to be for many days to come. Louis, who worked for Barclays Bank (D.C.& O), was a close friend of my parents, and had even stayed with them during his early days in Kenya. He gave me a very warm welcome, and on the very evening of my arrival, took me to visit some of the close friends and neighbours we had left behind some eleven years ago. Mr L. da Cruz (he was a widower whose wife had died shortly after my own mother) and his family were good friends of ours. The feeling inside me was now certainly one of great joy — it brought back many a memory of the happy days of my childhood — a childhood that was spent in our own home in Nairobi with my Mum, Dad and two brothers. I should mention here that my father had built a palatial house next door to the da Cruz bungalow. My dear mother, who was greatly instrumental in encouraging Dad to build the house, did not have the good fortune of living long in it. She died at childbirth in 1935, leaving my father a widower at the age of 35. I was six years old when Mum died, my elder brother Joseph, eight, while my younger brother Wildred, was only three. A shattering blow this was for all of us — to be deprived of a mother at such a tender age. For reasons best known to my late father, he had sold the house, with nearly an acre of land around it, for a very modest sum. To this day, none of us has recovered any money from this sale, and because of the unpleasant nature of the whole episode, I would prefer not to discuss this particular issue which must now remain a closed book. Suffice it to say that there were no documents or official papers for us to prove that Dad had not been fully paid for the house — all such documents being lost when the whole family died at sea. At the Secretariat the following day, I was taken to meet Capt. Wood by one of the senior Goan clerks. I was very well received by him. On this first occasion, I had worn the brand new suit which I'd had specially tailored in Belgaum. The welcome and reception I received from the many friends and acquaintances, is a fitting tribute to the high esteem in which my late parents were held. All this gave me a tremendous feeling of pride, and there were moments when I longed to embrace Dad and Mum and say a big "Thank you" for all they had done for us. They were parents I was truly proud of, and my determination was to preserve their good name at all costs. In the beginning, I was attached to the DCs (District Commissioner's) office at Nairobi, where I was given a variety of jobs, which included, among other things, the compiling of the new Voters Rolls for the district.

One of the senior Goan clerks — I think he was the Cashier at the time, a Mr Figueira, introduced me to the DC, an elderly gentleman by the name of J. Douglas-McKean. He struck me as a very kindly sort of person. I was told that he had not long to go before he retired. Even at the DCs office, there were frequent words of praise for my late father — not only from the Goan colleagues, but also the two African office boys who remembered him dearly. With obvious respect, they nodded their heads and said, "Oh, oh, mtotoya Bwana Maciel eh!" ("So this is Mr Maciel's son?") I was very touched by their expressions; I may have been new to the office, but certainly didn't feel lost. The people around me made me feel so much at ease and at home. This meant a lot to me especially when you consider that I was a mere junior clerk then. In Nairobi, I teamed up with three other friends who were allocated a wood and iron Government quarter in the Ngara residential area. Together we shared all the household expenses. Mr T. X. D'Cruz was the veteran among us, followed closely by the late Francis Ramos and Silvester Fernandes who I knew well from my school days in Belgaum. He was very much my senior though. All my three companions worked for the Kenya Secretariat. We had engaged a Kikuyu cook who produced average 'bachelor-type' midday meals for us, and in the evening, under the watchful eye of Mr D'Cruz (who was himself a good cook), Mwangi would turn out something more interesting and palatable! I cannot describe my excitement on receiving my first ever salary. Never had I seen so much money in my hands before! After quickly paying off my messing charges (Mr D'Cruz acted as a sort of 'general factotum'), I bought a brand new bicycle, using part of my salary, and the cash I had left over from India. The bicycle itself was a great boon since I used it daily to and from work. It provided me with some exercise and kept me fit. There was no expense for clothing as such, since I had arrived with a fairly new wardrobe — all the suits having been hand-tailored in Belgaum and Bombay. Tailoring was fairly cheap in India, and this is one of the reasons I had equipped myself with sufficient clothing to last me for a few years. After office hours, Francis Ramos and I would go along to the Goan Institute, which was then situated in Duke Street. It was here that I had my first real taste of beer. I must confess to not liking the 'bitter stuff at first, and wondered how so many of the club members were able to drink several bottles of it! All I was used to in India was soft drinks, so this drinking of beer was clearly a new experience for me. As time went by I got used to this popular liquid, but even so, the most I drank then was a glassful — never a whole bottle 2: Move to the Coast I had spent barely a couple of months in Nairobi when I asked my immediate superiors whether it would be possible to move me to the DCs office at Mombasa. Unofficially at least, I was told not to expect much, since people who were transferred to the Coast Province, were sent there more on health grounds (here, I am referring to the Goan staff in particular). Luck seemed to have been on my side, and within a few days, my transfer to the Coast Province was approved. I was simply delighted at the thought of returning to the warm and sunny climate of Mombasa, and of being with my cousins once more. Mombasa had a varied and interesting history; it was known as 'Mombasa Mvita' — the isle of war, and there is no denying the fact that this sunny town on Kenya's coastline witnessed, over the years, some bloody struggles involving Arabs, Africans and the Portuguese — all of whom were anxious to gain a foothold on the island. The DC at Mombasa was a very stern man I was warned. He was strict and expected a high degree of efficiency from his staff. So much for this rather awesome introduction to a man I had yet to meet! The only other thing I knew about him was that he was a New Zealander. My cousins were delighted to have me back, and though they had a young family of four children then, they readily agreed to my staying with them. On my first working day at Mombasa, I took the bus from Ganjoni (where we lived), to the town centre. On arrival at the DCs office, I reported to the District Clerk, Mr Cordeiro (a very tall and worried-looking man) who introduced me to the District Cashier, another tall, grey-haired elderly gentleman by the name of Albert D'Cunha. He was pleased to meet me, as was also my next contact — a Mr S. F. Braganca, a retired civil servant who, I was told, had been recalled to help with the additional work that had arisen in the office. As both these men knew my late father, I felt quite at home with them. The soft-spoken and well-mannered Mr Braganca had a very neat handwriting; he would have made a good artist. His was the type of handwriting that we were taught at school, and which I had great difficulty in transcribing. Sadly, my handwriting never improved over the years! Having met most of the Goan staff, I was then taken to meet the District Officer (DO) — the Hon. Roger Clinton-Mills, himself fairly new to Kenya; finally, I met the DC himself. There was no doubt in my mind, no sooner I had met him, that Mr Skipper was a tough man; earlier descriptions I'd been given of the man matched his serious countenance; he looked stern — rarely a smile on his face. In their white drill safari-type jackets and shorts, with well polished 'Kenya lion' brass buttons on their pockets, both the DC and DO looked very smart indeed. Since the DC and PC's officers were housed on the same floor, I also met some of the Provincial Commissioner's staff — first the chief clerk, Mr Pascoal D'Mello; an intelligent-looking individual, one of whose many duties included the posting of Asian staff within the Province. It was therefore very much in my interest to create a good impression, and this I was determined to do. I then met the relief clerk for the Province — a sprightly young man, 2 years my senior — his name, Ignatius Carvalho. This man was to become my loyal and trusted friend in later years. My duties also brought me in contact with some of the other officials in the district office — the Liwali for the Coast, Sheikh Mbarak Ali Hinaway (later Sir Mbarak Ali Hinaway), and also the Asst. Liwali at the time, Sheikh Rashid bin Azzan. I had more dealings with the latter with whom I also got on very well. He was a very kind and soft-spoken Arab who looked very impressive in his long flowing white robe. Mohamed Said was the Kadhi, and mention must also be made of our ever-obliging office boy, Fadhili, a native of the Coast Province, who looked old enough to be my father. He often surprised me with the speed with which he would attend to our many errands on his bicycle — official and private errands at that! I was never introduced to the Provincial Commissioner (PC) Mr E. R. St. Davies or the Deputy PC, Mr P. F. Foster, although I did know them by sight. Being new to the office, I was given an assortment of jobs — maintaining the inward and outward register of all correspondence, filing and correctly disposing of all incoming mail, etc. I welcomed the opportunity of doing the different jobs because of the training it provided me in the many aspects of the work in a busy district office like Mombasa. The District Clerk, Mr Cordeiro, was not a very healthy man and suffered frequently from attacks of asthma. This often meant that I, a comparative junior, had to step into the breach and take on a good deal of added responsibility. My efforts certainly didn't go unnoticed. I found that Mr Skipper would channel quite a portion of the daily correspondence and other jobs in my direction. This in itself gave me an added degree of responsibility which I knew would stand me in good stead in the years ahead. With the added experience I had gained, it was felt by officials at the PCs office, that I would now be suited for a posting to another district where I could work almost on my own. In many ways, I was delighted at the thought of being independent and having to fend for myself so to speak. This was the only way to get along in life I thought. As if to give me a foretaste of things to come, I was sent on relief duty to the Kilifi District situated half-way between Mombasa and Malindi. I was to assist the District Clerk who, I was told, was a very hot tempered individual. Fortunately for me, I never noticed any such traits in him, and must record that both he and his wife made my brief stay in Kilifi a very memorable and enjoyable one. Mr and Mrs R. R. D'Souza were a middle-aged couple who had no children; they were very pleased to have me stay with them. During my short stay in this district, I handled a lot of Court and Prisons work — a new experience as far as I was concered. In addition, I was able to assist Mr D'Souza generally in the office. The DC at the time was Mr J. D. Stringer, brother-in-law of Mr Skipper. Kilifi reminded me very much of my native Goa. It was here that I was able to taste some of the best cashews and cashew nuts too. Through the kindness of the D'Souzas, I was even able to visit the nearby town of Malindi, passing the Gedi ruins en route. These ruins are the first of the coast's long-lost ancient cities which were later uncovered and preserved. We made a brief stop here to survey the ruins, and later drove to Malindi where we spent the night. It was here I am told that the Portuguese navigator, Vasco da Gama, first stopped in the fifteenth century. Malindi is an idyllic little town full of unspoilt white sandy beaches. The music of the coconut palms swaying romantically in the gentle tropical breeze, the non-stop chatter of the Swahili folk at the local fish market, and the lavish hospitality of our Goan host, Mr Collaco (who owned an hotel at Malindi) are memories that haunt me still. Malindi has a large Arab and Swahili population, and is a well-known tourist attraction. As one approaches the Arab quarter of this small 'Arabian Nights-type' town, one can smell the salt fish-laden air, in distinct contrast to the fresh sea air in the more salubrious parts of the town. I returned to Mombasa having enjoyed my brief tour of duty at Kilifi immensely. The experience I had now gained in the many aspects of administration work had now made me 'eligible' for a transfer elsewhere. I had, in a way, come well through my probationary period, and the powers that be felt that I was fit to move out on my own. That they felt so confident, gave me added pluck and encouragement too. For me, it was a case of 'so far, so good'! Not surprisingly in late 1948, I was posted to Voi in the Teita District. I had heard a lot about Voi — notorious in days gone by for its malaria, a town where the grave of one of the victims of the 'Man-eaters of Tsavo' — Capt. O'Hara, still stands (and which I was able to visit). Voi also served as a junction for rail traffic bound for Tanganyika. I was delighted over this new posting, and left Mombasa by train on a Saturday, arriving at Voi a few hours later. I had passed through this station previously on my first trip to Nairobi. There to greet me were three Goans from the DCs office — the Cashier, Mr Silwyn Pinto, the District Clerk, Mr L. G. Noronha and the Rationing Clerk, a Mr P. J. DeMellow (who spelt his name differently from the rest of the D'Mellos — and who I was to replace). Accompanying them, was a rather serious-looking Goan, Germano Gomes by name, who was temporarily stationed at Voi while staff quarters and a district office were being completed at the nearby sub-station at Mackinnon Road where he was actually posted. Gomes, as I've said, looked very stern and gave me the impression of being a strict disciplinarian. I was not sure what to expect in the way of a reception, especially since the man I would be replacing, had had his services terminated. I never really found out why he was removed from office, nor did it worry me at the time since my prime task was to do the job I had been sent out to do. I must admit, however, to being somewhat embarrassed by the remarks of one of the Goans who had come to collect me from the station. Having driven down from the boma (administrative headquarters), in the government 3-tonner, he just couldn't understand how my luggage was so little — consisting of a large cabin trunk, a camp bed, mattress and holdall; that was all, nothing more! I wondered if he had realized that I was new to the service, and the things I had brought out with me were in fact the very items I had arrived with from India! This was, after all, my first job since leaving school, and the few possessions I had were my 'all and everything'. As I was to learn later, administrative staff who transfer between districts invariably carried 'tons' of luggage, and it was certainly a big joke among my colleagues — to see the 3-tonner being driven back to the boma almost as empty as when it had first arrived at the station. The driver of the truck, a fierce looking Mteita tribesman, with piercing eyes and distinct tribal markings all over his face, must have been equally amazed, but didn't utter a word. He merely grinned at me. Shingira was a very good driver, who I got to know and like. It was he who, in the months ahead, gave me my first driving lessons at the wheel of his 3-tonner. The hospitality I received from my friends was very warm, and after a brief stop at the house of Silwyn Pinto — where we were entertained to coffee by his wife, and where we also met Mrs Noronha — I was taken by Germano Gomes, later that night, to the Government bungalow which we would be sharing; a daunting prospect to be sharing this house with a man I held in awe. I needn't have feared though, since he turned out to be a very charming and hospitable individual. Despite the difference in ages, we got on very well. From my experience of Gomes in the office, I soon discovered that he was a glutton for work and a stickler for perfection. He was certainly not the person to suffer fools gladly. The surroundings at Voi were truly rural and I loved them. They made a pleasant change from Mombasa. From the rear of our bungalow, we looked out into the sparsely forested Teita Hills. The soil was ochre-like, and the ground itself seemed very parched. On the Monday morning, I met the DC — Mr K. M. Cowley, a Manxman from Douglas, Isle of Man. A very friendly and likeable person he really was, and I was convinced from the outset that I would have no difficulty in getting on with him. I was shown around my new office — a temporary mud and wattle structure with thatched roof, housing among other things, a collection of ants, lizards and other creepy-crawlies! I also had an office boy attached to my office — a Mteita tribesman called Mwambacha. An elderly and well-mannered individual, he was always willing to help in any way possible. The office boy at the main district office was also a Mteita by the name of Matasa, so was the tax clerk Douglas Mlamba. I was responsible to the DC for the issue of ration cards throughout the township, allocation of cereals, rice and sugar and, believe it or not, organizing the whisky quota among the Government and railway officials in the district. Scotch was strictly rationed in those days. I liked the job as it brought me in contact with the bulk of the townsfolk, chiefly the bibis (womenfolk), many of whom, babes strapped around their backs, queued patiently for their ration cards. These women wore very colourful dresses — some wore kangas (material for which was rationed and only obtainable against a permit signed by me on the DCs behalf). Mwambacha kept them all amused by indulging in their never-ending chatter. I dealt with the long queues as speedily as I could, but the worried look on Mwambacha's face often made me feel that I wasn't quick enough. I needn't have worried since I found out later that Mwambacha was very pleased with the way things were going — his worried look was part of his make-up since he always wore a solemn face! I was very impressed at the way in which he controlled the sometimes restless crowds, making sure there was no queue jumping. In addition to running the rationing office, I also looked after the district office stores. The stores ledgers and the stores generally were in one big muddle — no one had attempted to organize them, so I decided to make these my next priority. Mr Cowley was pleased with the initiative I'd shown, and gave me a free hand in the reorganization. After some weeks of hard work, I saw the DC and suggested that the best way to get the stores in ship-shape order would be to convene a Board of Survey — write off any minor losses and such items which had become unserviceable through fair wear and tear, and start afresh. He readily agreed, and soon after the Board of Survey had met and made its recommendations, I was able to start a brand new stores ledger with all stocks physically checked and recorded. Obviously impressed by what I had achieved in the short space of time, Mr Cowley was quick to commend me for my efforts. I felt greatly encouraged. Having thus spent a fair portion of my time organizing my work schedule, I found that I was free for varying periods during the day. I could, had I wanted to, have wasted this time in not doing anything constructive; the rationing office was a building completely separated from the main district office, so there was no direct supervision of my work as such. With all this time at my disposal, I volunteered to help both the District Cashier and District Clerk, since in addition to assisting them, I would be profiting by learning the various aspects of their respective jobs — an experience which would no doubt be to my advantage in the future. I do not think that either of them felt any sense of insecurity over my offer of help, especially since, judging from the rules for promotion obtaining at the time, it would be several years before I could be appointed to their grades. I must admit that the thought of displacing them never crossed my mind, and feel sure that the staff concerned were grateful for the assistance provided. On the home front, the senior clerk with whom I shared accommodation, Germano Gomes, was soon to move to Mackinnon Road. The DO, a Mr D. J. Penwill, had already moved there himself, and felt that he should have his clerk with him as quickly as possible. Gomes left within a very short time, and as a numerical replacement, and in order to step up the strength of the clerical staff at Voi, the PCs office posted Ignatius Carvalho (who I had previously met at Mombasa), as Asst. to the District Cashier. I was excited with the news of his posting as, being virtually of the same age, we would get on well together. Besides, our ideas about work and recreation were very similar. We even succeeded in dividing the domestic chores between us when Ignatius arrived. I managed the household budget, while he coped with, and very admirably too, the cooking and general housekeeping side of things. To assist us in the home, we employed a mtoto (Swahili term for juvenile) whose task it was to do the odd jobs around the house, i.e. the sweeping and tidying up of the house, shopping, and assisting generally with the cooking/washing up, etc. This young lad proved more of a liability at times. He would delight in helping himself to a bowl or two of rich soup, while we were treated to a highly watered-down version of the original recipe! We sometimes got quite exasperated and lost our cool, but soon came to accept the situation. After all, these were bachelor days, and there was precious little we could do to remedy the domestic situation. There was a great deal of outdoor activity to occupy our spare time; we often played tennis with the railway and post office staff; on occasions, the DC and some of the army personnel would join us. Another sport we indulged in was wild game hunting. The newly arrived Cashier, a Mr Andrade, a frontier veteran, possessed a firearm and also a bird/game licence, and we would frequently go on a dik-dik or buck shoot. Andrade was a crack shot who would have made an excellent marksman. We were never short of game meat while he was there. Our other recreation included a walk to the railway station each night in time to meet the Mombasa-Nairobi train. Here we often met the Postmaster and his family who lived not far from the station. Ed Ohis was a very jovial Mauritian who lived with his wife and grown up daughter in a house adjoining Voi post office. As Ignatius Carvalho knew many of the catering staff on the trains (his father having been employed in this department previously), we were very fortunate on occasions, to be treated to cups of that delightful railway percolated coffee. After the train had left Voi, we would return to the Ohis household to be entertained by soothing music from his guitar while I did the singing! At the office, several staff changes had taken place. The DC, Mr Cowley, had left on overseas leave, and was replaced by Mr A. J. Stevens (sadly, this young and promising officer was killed several years later when he went to investigate a border skirmish involving members of the East Suk tribe at a place called Nginyang in the Rift Valley Province). He was a much younger man than Mr Cowley. The District Clerk, Mr L. G. Noronha was transferred to Kwale, and his place taken by a native of the Seychelles — a Mr Popponeau. This latest arrival was fairly senior in the service, and had earned himself a reputation for introducing efficient filing systems wherever he went. He was a very methodical and conscientious worker. Relations with all the staff were very cordial, and although age-wise, Mr Andrade was the oldest, he certainly seemed the most active and energetic of the lot. Voi had no police station during my time, but a small force of six Kenya Police was stationed there under the command of a Sgt.- Major — Mohamed Lali, a Bajun from the Lamu district. Tall, tough and always smartly turned out, Sgt.-Major Mohamed Lali came directly under the DC as far as the day to day work and discipline was concerned; otherwise, his superior was the Superintendent of Police for the Coast Province who was stationed at Mombasa. An incident involving three off-duty Kenya policemen, and over which I had some dealings, needs to be mentioned. One evening when the DC, Mr Stevens, was away on safari, Sgt.-Major Lali came dashing to my house after office hours, with a familiar looking Government form in his hand. I immediately recognized this as being the one we always sent down to the local Medical Officer whenever there was a case involving 'assault causing actual bodily harm.' It so happened that the three policemen (all of the Nandi tribe) had got themselves so drunk that evening, that they attacked and savagely beat up a European farmer who had stopped briefly in the township on his way from Mombasa to his farm at Thompson's Falls in the Rift Valley Province. Dr. Jodh Singh, the local MO who examined Mr Swanepoel indicated the extent of the injuries on the form which was then returned to me by the Sgt.-Major. This would be required as evidence at a later date. As Mr Swanepoel had nowhere to sleep that night, Ignatius and I offered him the hospitality of our government bungalow — a gesture he much appreciated. After spending the night with us — obviously in great pain, he left the following morning. The next day, I reported the incident to the DC and the policemen concerned were charged and placed on remand. Their case was later tried by Mr Stevens in his capacity as First Class Magistrate, and the three were sentenced to 9 months imprisonment with hard labour, with a recommendation that they each receive six strokes of the cane. I was a principal witness in this case. Without in any way wanting to condone the action of these men, I felt very sorry for them. Here were three young men with a bright and promising future ahead of them — who had ruined their whole career because of drink. During our stay at Voi, Ignatius and I were very fortunate to make a trip to the Teita Hills, helping in the population census that was being conducted about that time. While in this area, we stayed at the Government Rest House at a place called Ngereni, high up in the hills at Wundanyi. On this safari, we stopped briefly at the main hospital at Wesu; the whole hospital area seemed always enveloped in a thick cloud of mist which kept lifting very slowly. Apart from the roads leading up to the Teita Hills, which were very steep and windy, the area itself was healthy, and there was talk even then of moving the administrative headquarters from Voi to Wundanyi (this transfer was achieved several years later). Due to Voi's proximity to Tanganyika, Ignatius and I were also able to visit the town of Moshi — thanks to a kindly Arab trader (Shariff Ali) who ran a regular bus service between Voi and Moshi; I recall having a haircut there since we did not have a resident barber at Voi! Yet another sub-station where I was fortunate in being able to do a spell of relief duty was Taveta on the Kenya/Tanganyika borders. This district was well known for its sisal plantations and one of the early European pioneers, the late Col. Ewart S. Grogan lived here. Although my stay at Taveta was very brief, the young Goan cashier (Peter de Souza) and his wife were perfect hosts to me. The DO at the time was a Mr A. D. Galton-Fenzi, a tall and well-built young man who always seemed so full of energy. He and Peter de Souza were greatly instrumental in having a tennis court built at Taveta with the help of prison labour. The District Cashier prior to Peter's arrival was a middle-aged Goan called Ivo Coelho, who was a good friend of ours. As bachelors, Ignatius and I found that our house was regularly being used as a sort of 'entertainments centre'. While we were happy to entertain our guests, the frequency of such 'get togethers' was beginning to make inroads into our meagre finances. Under the existing rules governing advancement within the service, there was no prospect of our receiving any substantial financial reward (other than the annual increments) for some considerable time. Seniority was the main criterion for promotion in those days. Although in our own minds we knew we were doing a good job, and certain that our immediate superior was aware of this, we did realize that, as newcomers in the service we could hardly expect to receive any preferential treatment. The only solution was for us to move to a district where there was not too much of a social life, and where we could live relatively debt-free. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Part Two: A Taste of the N.F.D. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

3: Turkana District We had heard of inducements made to those who served in the N.F.D. One received a hardship allowance of Shs.4/- per day in the case of the Asian staff, while the European staff received Shs.6/-. I could never really understand the inequality of this allowance especially since we endured the same hardships and inconveniences as our European colleagues. In some cases, I feel the Asian staff were at a greater disadvantage. A further attraction of a frontier posting was the certainty of being granted an interest-free advance of 3 months' salary, repayable over a period of 12 months. The purpose of the loan was to enable staff to buy a good supply of tinned food and other necessities in advance of their posting; this was because many of the commodities that were freely available elsewhere in Kenya, were either in very short supply or just not obtainable in some of the frontier stations. The granting of the loan itself was a mere formality, but application had to be made none the less. Ignatius and I lost no time in applying for a posting to the frontier, much to the surprise of local colleagues and, I daresay, staff at the Secretariat; very few, if any of the Asian staff ever applied for a posting to the N.F.D. Surprisingly, and much to our delight, within the space of a few weeks of our applying, our posting orders had arrived. I was transferred to Lodwar in the Turkana district (on the Kenva/Uganda/Sudan borders), while Ignatius was to go to Wajir in the heart of the Somali country, not far from the Italian Somaliland border. Our salary advances were approved and a major portion of this was utilized to purchase various provisions and other requirements for our new stations. Owing to the remoteness of frontier stations from the nearest down country base, staff were expected to carry adequate stocks of food, drink and other domestic requirements. In the words of the then Provincial Commissioner, anyone borrowing from a fellow-officer — be it a can of corned beef or a bottle of kerosene oil, was "making an infernal nuisance of himself". A harsh directive surely, and one that couldn't be taken lightly! The days prior to our departure from Voi were pretty hectic; we had made many friends during our stay in the district, and were naturally sorry to leave them behind. Not only did we have friends at Voi, but also in the surrounding areas of Mwatate and Bura (where the Catholic Mission was situated). Our last days were taken up attending several farewell parties which friends from all walks of life had organized for us. It was very comforting to feel the warmth of friendship so manifest in the hospitality we received everywhere. Even the Teita Vegetable Company (an African co-operative venture), from whom most of our vegetable supplies came, had sent us a basketful of freshly picked vegetables of various kinds. I was quite fond of the Mteita tribe and my cook-cum-housebov, himself a Mteita, asked if I could take him along to Lodwar. Since neither of us knew what was in store for us at the other end, I readily agreed to his joining me, but warned him about the climate and lack of amenities, etc. Lodwar was the direct opposte of the Teita Hills area from where Daniel came, but the thought of going to this inferno didn't seem to worry him unduly at the time. There was not much to do in the way of packing since neither of us had much luggage. I left ahead of Ignatius, especially since we were going in different directions — he to Wajir via Nanyuki and Isiolo, while I had to go via Nairobi, Nakuru and Kitale to get to Lodwar. The journey from Voi to Kitale (the nearest down country base for the Turkana district) was quite tiring. I had left Voi at night and arrived in Nairobi the following morning. As one leaves Nairobi and enters the Rift Valley Province, stopping briefly at some very interesting and well-maintained stations en route, one couldn't help noticing the change in the vegetation. Some of the richest farming areas were to be found in this region — the 'White Highlands'. Many of the station names were familiar to me — Naivasha, Gilgil, Nakuru and Eldoret. Kitale was a truly farming town which bustled with a lot of activity every week when farmers from the nearby areas of the Cherangani Hills, Endebess and even Hoey's Bridge, would come in to deliver their cereals to the big co-operative store — the Kenya Farmers' Association (or K.F.A. as it was popularly known). Dairy farmers would bring in their milk and cream supplies to the Kenya Co-operative creameries from where was produced some of the best known Kenva butter, cream and cheese. After seeing the large farms that many of the European settlers owned, the prize dairv herds they kept and the sheer richness of the land, I realized why they wanted to keep the Highlands all for themselves. Who wouldn't, given the excellent climatic conditions? The fact that I had old family friends at Kitale made matters much easier for me accommodation-wise, and I was happy to be in a family environment once more, and taste the delights of good home cooking from the hands of a grand old lady (Mrs C. H. Collaco) who, many years later was to become my mother-in-law! I stayed here for two days — thanks to the hospitality provided by the Collaco family, and left for Lodwar on a 3-ton army type truck belonging to the local Government transport contractor (A. M. Kaka), on the afternoon of May 29th 1949. Mr Kaka, a staunch Muslim, had been the Government contractor for the Turkana district for many years; through very adverse conditions, and at great personal risk, he had carried on the transport business, starting with a modest Ford V-8 truck, and later ending with a fleet of modern vehicles. These lorries were rightly his pride and joy, but the envy of some of his competitors who now wanted to enter the transportation scene themselves. Kaka's success was due to sheer hard work, and he had earned himself a reputation for reliability and dependability — attributes so essential if any business is to succeed. His trucks plied almost daily between Kitale and the various parts of the Turkana district, notably Lodwar and Lokitaung, with the occasional trips to the lake and even further north to Namaraputh. He was regularly awarded the Government contract for carrying mail, personnel and other supplies. He had served the Administration well and efficiently and was well liked and highly respected in the district generally. There was never any reason to look for an alternative contractor judging from the excellent service he had provided all along. The monopoly over transport that Kaka enjoyed certainly caused a good deal of resentment in later years among some of the newer traders who were now beginning to gain a foothold in the district. Despite his wealth — and there is no denying the fact that Kaka was quite a rich man — he was a very modest and unassuming individual, whose pleasant manner and willingness to help impressed me greatly.